As part of the Sacred Himalaya Initiative, ICI scholars and research assistants collected numerous folk stories from across the KSL region. Based on the stories collected over three years, two books of folk stories from the region were published. One book is titled Shared Sacred Landscapes: Stories from Mount Kailas, Tise & Kang Rinpoche and the other book is titled Folk Gods: Stories from Kailas, Tise & Kang Rinpoche. Cover images for both books are shown below.

The books were published in 2017 by Vajra Books in Kathmandu, Nepal. The Shared Sacred Landscapes book [buy online] is edited and re-told by noted authors Kamla K. Kapur and Prawin Adhikari, and includes 7 stories expanded upon by the authors. The Folk Gods book [buy online] features 10 original folk stories retold by Prawin Adhikari. Each book was published in translations with Hindi, Nepali, Tibetan and Mandarin. You can purchase hard copies of the Shared Sacred Landscapes and Folks Gods books at the Vajra Books store in Thamel, Kathmandu.

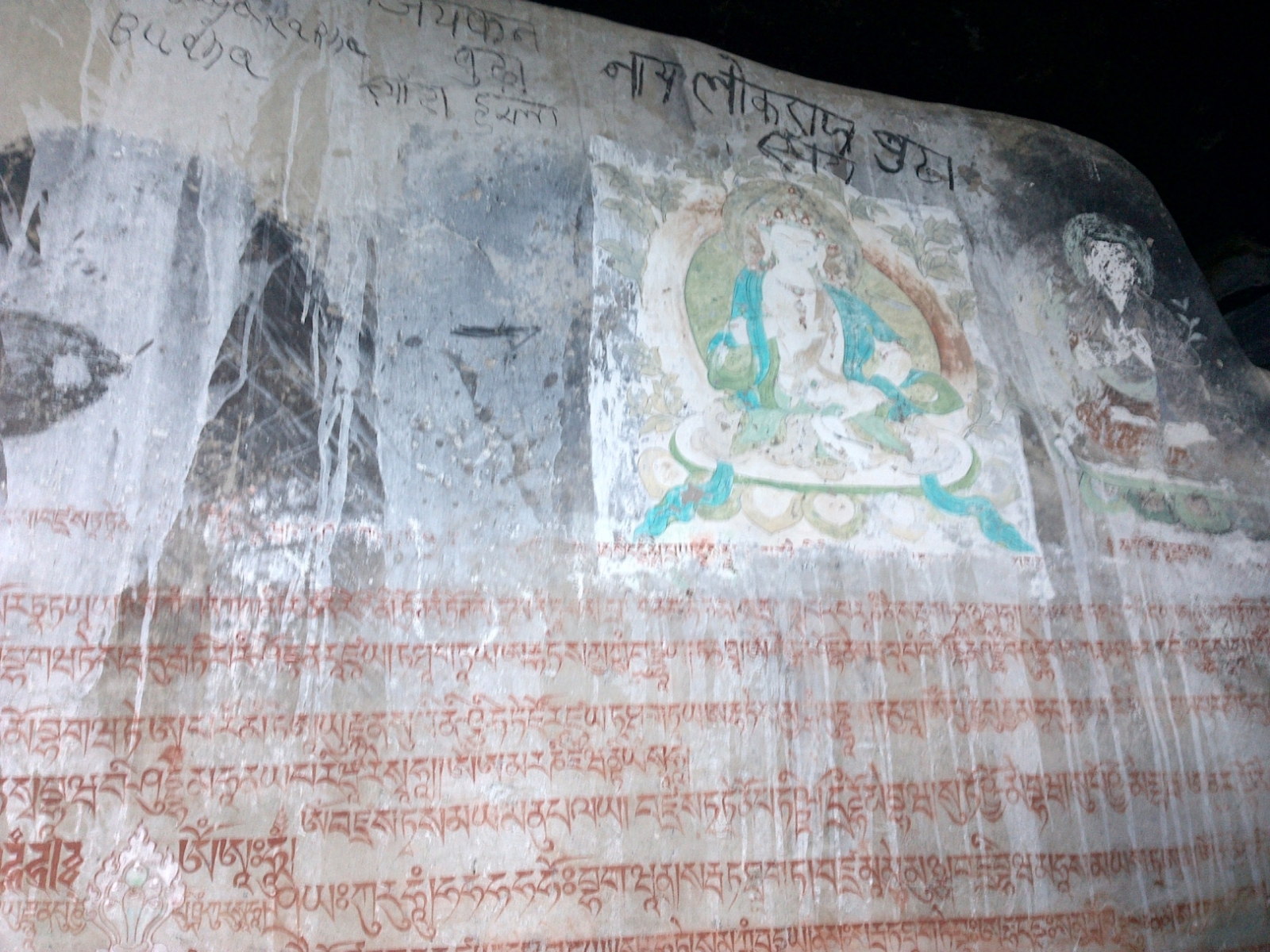

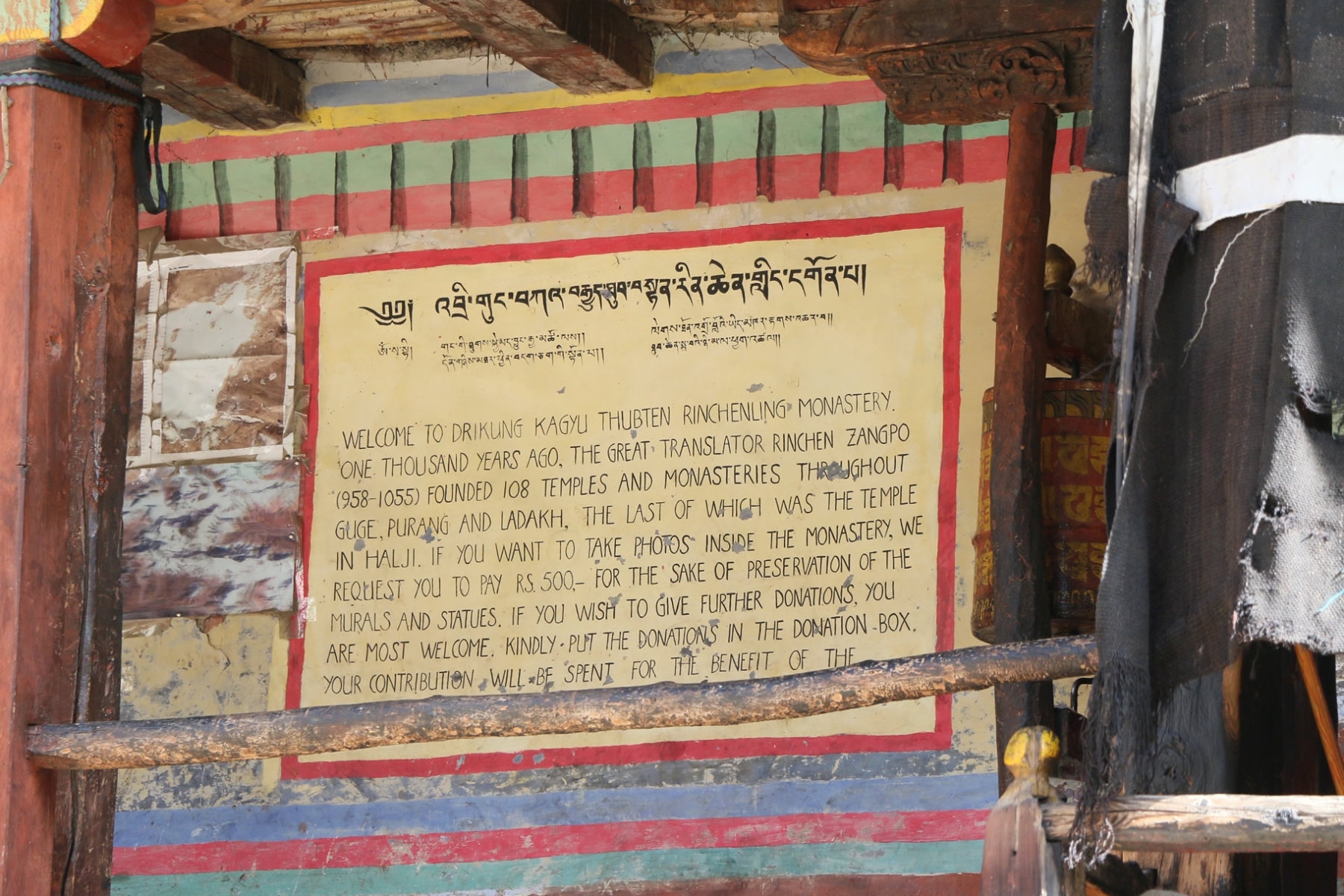

|

|

As part of documenting these folks stories for historical preservation and cultural learning, ICI and ICIMOD are making all of the stories included in these collections available for public access and use over several years following publication (2017). After May of 2019 all of the story text will be made publicly available under a Creative Commons license. As the stories become available they will be included below, with a link to the pdf file for each story and its translations.

Excerpts from individual stories, as well as pdf links to the currently available full stories, can be found below. Click on the + menu items to see more information.

Shared Sacred Landscapes

Stories from Mount Kailas, Tise & Kang Rinpoche

You hold in your hand a unique book of stories about a very special shared sacred landscape. This book celebrates and acknowledges the power of folk stories, which are amongst the most valuable treasures that one generation can pass onto the next. Folk stories inscribe collective meanings, give credence to cultural beliefs, and are an integral part of how a community understands not only its history and traditions, but also articulates its future goals and aspirations.

In publishing this book we wanted to draw attention to the uniqueness of this remote yet intensely revered region. Th is particular Himalayan sacred landscape is of equal importance to Bönpos, Buddhists, Hindus, Sikhs, and Jains. For example, Hindus refer to the most significant mountain within this sacred landscape as Kailas, the abode of Lord Shiva; Bönpos refer to it as Tise, and Tibetan Buddhist refer to it as Kang Rinpoche.

By bringing the narratives, peoples, and sacred landscapes together, we want this collection of short stories to convey to the reader some of the significance of the holy mountain and its surrounding regions. We also want to show how local knowledge illuminates the multiple connections and various traditions between religion and ecology, time and space, the past and the future. By making these stories available – both in print and digitally – we want to ensure that the folk traditions of this unique region are voiced, preserved and made accessible for future generations. Th is volume, as well as the online depository of many more collected folk stories, are available on the website of the India China Institute.

The original versions gathered from this shared sacred region were often quite short in length, and, as is often of the case with folk stories, narrated with many variations. The primary sources of these stories — men and women, shamans, elders and priests in Humla, Ngari and Pithoragarh were informed that the material collected from them would be made freely available to readers and researchers around the world, and that their stories may be selected for retelling by writers, or for dissemination through the internet, or for educational purposes.

Because many of these stories transcend and overlap physical, spiritual, and cosmic boundaries, we invited two noted writers, Kamla K. Kapur and Prawin Adhikari, as special Editors to retell and situate the stories in the larger context of Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain and Bönpo traditions. We are grateful to these two writers whose amazing talents flow through the pages of this book. In addition to these retold versions, readers also have the opportunity to access the original stories, including additional audio and video material, on the website of the India China Institute. As a way to honor the places where they were collected and to also make them accessible in the vernacular, select stories appear in the English as well as in the Tibetan, Nepali, or Hindi language.

This book emerged out of a three-year project designed and led by the India China Institute (ICI) at The New School in New York City and based on collaboration between The New School and the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD). It is the product of a collaborative endeavor with ICIMOD’s Kailas Sacred Landscapes Conservation and Development Initiative (KSLCDI), a transboundary conservation and development initiative working to strengthen regional cooperation among China, India and Nepal. ICIMOD’s team Abhimanyu Pandey provided insight into the anthropology of the region, Rajan Kotru provided a platform to meet and interact with associated colleagues, and Swapnil Chaudhari coordinated with the team. Special thanks to Toby Alice Volkman at the Henry Luce Foundation for her intellectual contributions and support for the project. I want to use this opportunity to thank all of our supporters for their partnerships and generous contributions. Also a very special thanks to our fieldwork team: Sagar Lama, Himani Upadhyaya, Kelsang Chimee, Kunga Yishe, Pasang Y. Sherpa, Sheetal Aitwal, Nabraj Lama, Abhimanyu Pandey, Shekhar Pathak, and Tshewang Lama (Chakka Bahadur) – for their crucial role in gathering stories from the region. Th anks to Tenzin Norbu Nangsal for editing the Tibetan and Shekhar Pathak for editing the Hindi. I also want to acknowledge our Grace Hou and the rest of the India China Institute staff for all their support. In addition to contributions from Th e New School, primary support for the project came from the Henry Luce Foundation and additional support from the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD).

This project involved a unique collaborative effort with over twenty scholars and experts from many parts of the world and different disciplinary backgrounds – anthropology, international development, history, geography, arts, and politics. Some members are from the Himalayan region and have a deep connection to our work of the Sacred Himalaya Initiative (Shekhar Pathak, Tshewang Lama). Others have had extensive professional engagement in the Himalayas (Mukta Lama, Kelsang Chimee, Ashmina Ranjit, Anil Chitrakar, Kunga, Pasang Y. Sherpa, Ashok Gurung, Kevin Bubriski, Srestha Rit Premnath, and Amanda Manandhar-Gurung). We also invited scholars with no prior work in the Himalayas, but who nevertheless have deep knowledge and interest in the relationships between ecology, culture and religion from a global perspective (Mark Larrimore, Rafi Youatt, Nitin Sawhney, Chris Crews, Liu Xiaoqing, and Marina Kaneti).

Over the course of three years, between 2014 and 2016, members of our group engaged in several pilgrimages and field trips in and around the Kailas Sacred Landscape of India, Nepal, and Tibet. We spent many weeks hiking through the Himalayas at an average elevation of over 3,800 meters (12,500 feet). Encounters with the natural landscape, pilgrims of various faiths, and travelers drawn to the rugged beauty and serenity of the region shaped our understanding of this unique landscape as a shared sacred space. From the very start of designing this study in 2013, we were drawn to the significance of multiple and oft en overlapping meanings and imaginaries of this shared sacred mountain, both for people who inhabit the region as well as those who come from outside. We hope that our work will provide a glimpse into the unique traditions and cultures of this region. As you will discover throughout this book, many aspects of these ancient stories continue to inform the sociocultural traditions and everyday interactions of millions of people in the region. The stories allow us to better understand the revered past and the ways in which the Himalaya is connected to contemporary global questions of climate change, biodiversity, and sustainable futures. They show the various ways in which the past and the present, humans and nature, gods and animals are intricately and eternally connected. The stories inspire the reader with a yearning for meaning in life beyond one’s own desires and needs.

As this shared sacred region becomes more accessible – both physically and digitally – many important questions emerge about its future. As the principal investigator of a project so intricately involved with this region, I will always treasure this once in a lifetime learning opportunity. As a member of the Gurung ethnic group from the highlands of Nepal who was raised in the Indian Himalayas and worked in Tibet, and as somebody steeped in the diverse traditions of Buddhist lamas, Hindu priests, and Animists, this project also resonated for me on a personal level. It allowed me to revisit and rediscover stories about Lord Shiva, the Goddess Parvati, Mount Kailas, and Lake Manasarovar that I had heard about as a child. Finally, as an academic, the project broadened my understanding of the many-layered and oft en contested meanings of the shared sacred region. Th ere is no substitute to experiencing firsthand the various ways in which the region itself transcends both physical and temporal boundaries.

My hope is that the stories in this book will similarly allow readers to discover, or perhaps rediscover, this region in all its human diversity and sacred timelessness.

In these varied ways, our project went beyond just storytelling and brought a sense of what connects the peoples and the traditions of this region. It inspired us to think beyond state and national boundaries and to submerge ourselves in the vast universe of complex co-existence between so many different peoples and cultures.

The process of telling and retelling stories is always a group effort. This book would not be possible without many individuals sharing their time and stories with us. These folk stories were collected over the course of three years of exploration in the Himalayan areas of India, Nepal and the Tibet Autonomous Region of China. The stories were shared with our research team in many places—on dirt paths in the mountains; in communal halls around a fire; with locals one-on-one in their homes; and in meeting with lamas, priests, storytellers and village elders. It was oft en the case that we would hear the same story told in multiple versions. Two well-known writers, Kamla K. Kapur and Prawin Adhikari, took these stories and gave them new life. We are very grateful to them. Most importantly, we would like to express our deep gratitude to the local villagers who shared their stories for the benefit of future generations. What you hold in your hands is the result of this collective effort. More information about the individual team members who collected the stories is included in the Introduction.

We also would like to thank the talented translators who helped make sure these stories would be understandable in each local language: Samip Dhungel, Rajendra Balami, and Kriti Adhikari (Nepali); Kelsang Chimee (Chinese); Bhuchung D Sonam and Thinlay Gyatso (Tibetan); and Chandresha Pandey (Hindi).

Journey to Bone and Ash

Collected from Chaudhans, Uttarakhand, by Himani Upadhyaya from Dhiren Budhathoki. Retold by Kamla K. Kapur. Translated into Tibetan by Bhuchung D. Sonam.

The Color of the Name

Collected from Chaudhans, Uttarakhand, by Himani Upadhyaya. Retold by Kamla K. Kapur. Translated into Hindi by Chandresha Pandey.

You Don’t Die Till You’re Dead

Based on a Tibetan story recounted by Tshewang Lama (Chakka Bahadur) of Humla. Retold by Kamla K. Kapur. Translated into Hindi by Chandresha Pandey.

Attitude of Gratitude

Collected from Dharapori, Humla, by Sagar Lama from Krishna Bahadur Shahi. Retold by Kamla K. Kapur. Translated into Nepali by Kriti Adhikari.

Ripples on the Mirrored Lake

Story told by Po Wobu, Ngari, Tibet Autonomous Region. Collected by Kelsang Chimee. Retold by Prawin Adhikari. Translated into Tibetan by Thinlay Gyatso.

Godsland

Based on conversations with dhamis Man Bahadur Shahi, Tul Bahadur Shahi and Suvarna Roka of Humla. Written by Prawin Adhikari. Translated into Nepali by Samip Dhungel.

The Miller’s Song

Based on a story told by Kharkyap Dorjee Lama of Yari, Humla. Collected by Sagar Lama. Retold by Prawin Adhikari. Translated into Nepali by Rajendra Balami.

Kamla K. Kapur

Kamla K. Kapur was born and raised in India and studied in the US. Her writing has included plays, novels, poetry, essays and reimagining Indian spiritual writings. Her critically acclaimed books include Ganesha Goes to Lunch: Classics from Mystic India (2007, Mandala, USA; also retitled Classic Tales from Mystic India, Jaico Publishing, 2013), Rumi’s Tales from the Silk Road, Pilgrimage to Paradise (Mandala USA and Penguin India, 2009), and The Singing Guru, on the legends of Guru Nanak (Mandala USA, 2015). Her highly praised books of poetry are As a Fountain in a Garden (Tarang Press, 2005) and Radha Sings (Dark Child Press, 1987). Her poetry and short stories have appeared in Yellow Silk (Berkeley, California), Journal of Literature and Aesthetics (Kerala), and the anthology, Our Feet Walk the Sky (Aunt Lute Press, Berkeley, California, USA). Kapur was a semi-finalist for the Nimrod/Hardman Pablo Neruda Poetry Prize competition in 2006, and three of her poems were published in Nimrod, International Journal of Poetry and Prose (2007). Five of Ms. Kapur’s short stories were published in Parabola, journal of Myth, Tradition, and the Search for Meaning (New York), two in The Inner Journey, (Parabola Anthology Series, 2007), and one in The Sun (USA, December 2012) Ms. Kapur divides her time living in the remote Himalayas and in San Diego, California, with her husband, the artist Payson R. Stevens. Visit her website.

Prawin Adhikari

Prawin Adhikari writes screenplays and fiction, and translates between Nepali and English. He is an assistant editor at La.Lit, the literary magazine. He has translated Chapters (Promilla & Co., 2011), a collection of short stories by Amod Bhattarai, and A Land of Our Own by Suvash Darnal (LSE, 2010). His collection of short stories The Vanishing Act (Rupa, 2014) was shortlisted for the Shakti Bhatt First Book Prize. His stories and translations have appeared in publications like The Open Space and in House of Snow, an anthology of Nepali writing. His translation of short stories by Indra Bahadur Rai is forthcoming from Speaking Tiger.

Journey to Bone and Ash

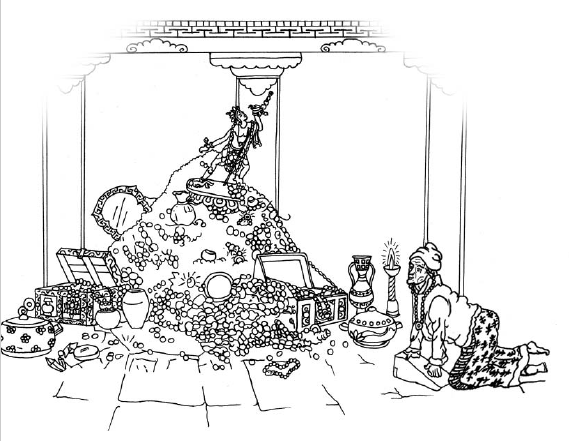

Original illustration by Rabin Maharjan.

There was once an old woman called Dechen. People called her Dechen Budhi – Dechen, the old woman. She wasn’t always old, of course. Once she was youthful, vibrant, very beautiful, with a slim, slight figure, high cheekbones, dimples, unusually large, dark eyes, smooth, clear skin like ivory, and thick, black hair. She took pride in her beauty and youth. A singer and dancer, she was adored and worshipped by men, and envied, if not hated, by women. The men courted her and lavished gifts and money on her, which she managed very carefully because she had known extreme poverty while she was growing up in a large family. She had eight siblings who were always inadequately clad, and she had experienced the death of two in the freezing winters. As a child Dechen was always hungry, like her brothers and sisters.

It was the custom of her polyandrous tribe for one woman to marry three or four brothers. “Even one husband,” she could hear her dead mother’s voice in her head, “is one too many. Managing four has brought me to an early grave.”

Dechen had determined early in life not to marry but support herself by her own talents, and because she had many of them, she became very wealthy.

Dechen worshipped all the gods of prosperity: Pehar, Ganesha, Lakshmi, and all the Naga goddesses who generate and protect wealth. She buried her money under straw and grass piles on the ground floor of her three-story stone, wood, and mud house, the floor of which was used by cows, yaks and sheep. She even kept a few yaks and dogs on that floor to deflect attention from her secret hiding place, and hired the village idiot as a servant to graze and tend them.

In her mid-twenties, Dechen supplemented her wealth by weaving and tailoring woolen dresses that were much in demand. Both men and women wore them all year long in the high desert plateau where they lived. She also began to make chhang, the favorite stimulant of people in the winter months when the high plateau, home to some of the highest mountains in the world, was freezing cold. Dechen’s chhang, however, was much more than just local beer made with barley. Using her grandmother’s secret recipe, she fermented it with the best of yeasts and infused it with the highest quality cloves, cinnamon, nutmeg, cardamom, pepper and ginger. Moreover, she made it from the waters of Manasarovar, the healing, holy lake at the foot of the great Kailas Mountain, home of all the gods and goddesses of the Hindus, Tibetans, Jains and the indigenous Animist religions. Many swore Dechen’s chhang was a tonic that cured them of colds, body and joint aches, stiffness and indigestion. People traveled far to buy it from her at a high price, and it swelled her wealth a hundred fold.

Because Dechen did not believe in sharing – a habit she had developed early in life on account of having altogether too many siblings to share food and clothing with – by the time she was thirty, not an inch remained beneath the entire mud floor that didn’t have a thick wad of money or bags of coins. She had to find other secret places to store it all. She sacked the village idiot for fear he might accidentally discover it, got rid of her yaks because she didn’t want to risk leaving her house to graze them, and spread a rumor that all her wealth had been stolen, and a lot eaten by silverfish. To confirm her lie, she began to wear rags even though she had exquisite dresses of Chinese silk and woolen brocade hoarded away in wooden trunks. She also pretended to be mad as a result of the “theft” of her money.

Dechen had no friends, but she didn’t care. She was self-sufficient and content with her wealth, the very thought of which was enough to send her into paroxysms of ecstasy. She spent her time hollowing out the legs of her bed and the frames of her looms to hide her money in and boarding up the windows.

In her early thirties, upon seeing a woman in the haat wearing an exquisite necklace made of gold, lapis, turquoise and coral, Dechen’s lust for gold objects and jewelry was aroused. She decided that it wasn’t enough to just have money that was hoarded away in various secret places of her home. She wanted to buy lovely objects that she could see, touch and admire – something real, solid, material and lovely.

For many years, with her house safely boarded up, she traveled far and wide, to India, Nepal, China, to find and buy up rare treasures made of gold and precious stones. She brought back her purchases– jewelry, mirrors, jars, boxes to hold her spices, finger rings, earrings, necklaces, and gold images of the gods and goddesses of wealth – hidden in ragged-looking gunny sacks filled with rice, kindling, lentils and dung.

She placed the gold statues of the gods and goddesses of wealth on an altar, bowed to and worshipped them three times a day: Lakshmi; Ganesh adorned with garlands of gems, his rat regurgitating jewels; Demchong Chintamani, guardian of wealth, holding the luminescing wish-fulfilling jewel of abundance in his hands. She had fallen in love with a statue of Vajrayogini, a female Buddha, and even though the goddess was not associated with wealth, she had bought it impulsively. It was only much later she saw some disturbing elements in the statue: Vajrayogini held the curved driguk, a fierce- looking flaying knife in her right hand, and the kapala, a skull cup in her left as she danced in fire. But because Dechen had paid so much for it, she kept it and placed it on the altar.

Buying, organizing, arranging, dusting, admiring her home filled with her precious purchases for hours on end in the light of the yak- butter lamps that illumined her dark house became Dechen’s whole life. Her other favorite preoccupation and passion was wearing her silk brocade gowns, adorning herself with necklaces, earrings, nose rings, and admiring herself in her jeweled mirrors. How proud she was of having fulfilled her heart’s desire to be wealthy and never lack for anything! How proud she was of her beauty! Her intense attachment to her youth, her wealth, and her home were enough to give purpose to her life.

Dechen didn’t realize then that having too much, and not sharing it, is worse than not having enough. She couldn’t see how her obsession had made her a captive in her own home. She often wished she could hire servants to help with her many tasks, but since she didn’t trust poor servants not to steal her things – any one of which would have helped them retire and live well for the rest of their lives – she had become her own servant and slave.

One day, however, as Dechen was sitting on the balcony on the third floor of her over-stuffed home, overlooking a playground in the village in which young children were playing, accompanied by their parents or older siblings, she felt something she hadn’t felt before. She couldn’t describe the feeling, but the first symptom of it was that she felt dreadfully lonely. She hurried inside to her pretty objects, lit her candles, and hoped they would cheer her up, but they failed to do so. The solitude to pursue her material passion turned into a haunting aloneness in which the walls of her self-made prison seemed to close in upon her.

A big, dark, frightening emptiness opened up inside her and she was certain she would fall into it and drown. As this was such a horrible feeling, and as she hadn’t yet learned to give each feeling its due of attention and introspection, she now did everything in her power to ignore it, lock it up, throw it away, bury it.

But because she had buried a living and kicking feeling, it kept resurfacing, again and again. The only way she could think of banishing the feeling was buying more lovely things. So, wearing her rags and a cheap necklace of glass beads around her neck, she went on another tour. She bought turquoise artifacts and jewelry from China, amber beads from Tajikistan, coral and pearl necklaces from India, heaps and mounds of treasure to take back to her home.

Living her life the only way she knew how, without thought and reflection, Dechen didn’t notice how Time was weaving its invisible net inside her body till she woke up one day and saw it in her jeweled mirror: a network of wrinkles crisscrossing her face like the gossamer threads of a spider that had caught her eyes, nose, mouth in its web; gaps where her teeth had fallen; the thinning, grey hair on her head. She turned to another mirror, and yet another: each of them had turned traitor and reflected the same image of a face ravaged by time. Dechen threw them away in disgust; people started calling her Dechen budhi, old Dechen, and paagal budhi, the crazy old woman.

The old feeling of despair rose from its grave and haunted her in nightmares. She dreamt about missing caravans because she couldn’t pack her enormous treasure in time to take it along with her, of not having enough mules to pack them on, of thieves breaking into her home and carrying it all away. These nightmares were mild in comparison to the darkest ones that emerged from the crack in her psyche: gods and goddesses she worshipped to fulfil her material lust turned hostile and came to her as dark, evil, wrathful, demonic forces bent on destroying her. Demchong, Mahakal, came to her with the ashes of the dead spread on his body, beating his drum louder and louder as he did his dreadful dance of destruction, and trampled Dechen underfoot; Vajrayogini came, her fierce third eye spurting fire that burnt down Dechen’s house with Dechen in it, turning it all to ash. In yet another nightmare Vajrayogini stepped on Dechen’s body, bent her head downward, snapping it till it reached down to her heart. In another she flayed Dechen with her knife, catching her blood in her skull cup and drinking it as if it were the most delicious of wines. Dechen felt possessed, taken over, inhabited by dark and evil forces.

In her desperation she called for a Buddhist Lama to do a kurim, an exorcism, to expel the evil spirits. He came with his dorje, a two- sided metal arrow, and phurbu, a staff, to drive them away and release Dechen from hell. But though the ceremony was elaborate and expensive, her nightmares continued. Next, she went to a dhami, the local spirit medium, and a dangri, an interpreter of the messages received by the dhami. The two would charge a great deal for their services. Besides, goats would have to be sacrificed and cooked for the village. Dechen was very reluctant to part with any of her wealth.

She would rather have bought another gold object. But on the verge of madness, she decided to go ahead with it.

With ashes smeared on his face, matted hair coiled on his head, the laru, a long hairpiece wrapped with silver threads, draped around his head and neck like Shiva’s snake, a trident in one hand, and a two- sided damaru drum in the other, the dhami began the ceremony after drinking copious amounts of chhang. The dangri and dhami both beat their drums, accelerating from a slow and steady rhythm to a maddening tempo that chased all thoughts away from Dechen’s head.

The dhami shook his hair free, his eyes rolled up in their sockets, his body quivered, his movements became spastic and uncontrolled as he went into a trance. He began to dance, laugh and cry as the gods and goddesses entered him, talking simultaneously and cacophonously. He began to make pronouncements in a language that was neither Nepali, Kumaoni, Tibetan, Hindi of Hoon, nor any recognizable dialect. Dechen couldn’t understand a word. She looked to the dangri, who had the skill to interpret what sounded like gibberish to most people. He was silent a long time, trying to decipher the words while Dechen stood by them, looking lost and confused.

“The gods and goddesses are saying you have poverty of the soul.

You must die.” the dangri said.

Dechen felt a bolt of fear shoot through her. Her knees gave way and she fell in a heap on the ground, weeping and wailing.

“But isn’t there anything I can do? I don’t want to die!” She wept as thoughts about leaving behind her precious treasure stung her brain like serpents.

The dhami muttered some more, and after a pause the dangri said, “It seems like a waste but he says you should throw all your valuables into the Dhauli River. Or you will go mad and then die.”

Dechen was devastated by the message. Her long-cherished treasure, dumped in the river! No, she thought, this was a plot by the dhami and dangri to divest her of her wealth. They would waylay, loot and kill her.

But as the days passed, her state of mind worsened. After much deliberation and vacillation she decided that very night to take a muleload of her wealth to the river. She packed gunny sacks with the first objects to fall into her hands, boxes full of jewelry, tea sets and jugs made of gold, and loaded them on the mule.

The moon lit the path as she made her way to the river in the middle of the night and very reluctantly dumped the contents of the sacks into the swift waters that carried them away.

Meanwhile, from the other shore, a man watched an old woman wearing a ragged go pung gyan ma, gown, a worn hat and shoes, remove sacks from her mule, and empty glittering objects into the river. After she left, he went to the spot and saw them being swept away. He waded in and retrieved a gold box full of jewelry. He was baffled, and decided to see if the event repeated itself the next night. This time Dechen decided to rid herself of all the gods and goddesses from her altar. It was a beautiful night as she stepped out of her house with her mule loaded down with sacks. The moon was almost full in its reflected radiance, bright and lovely despite its blemishes, its orb floating past a dark cloud edged with golden light as if pushed by the gentle breezes flowing down through high mountain passes.

As she arrived by the banks of the Dhauli River and unloaded a sack, a man came towards her. Dechen was dreadfully afraid: he was going to kill her and steal all her things! But the thought that disturbed her much more was: “I can’t die now! I haven’t lived yet!”

“What are you doing?” he asked her.

Dechen was stunned by his words. Nobody had ever taken the trouble to ask her, nor had she ever asked herself this question. His words came to her like a revelation, peeling away hardened scabs on the many wounds of her heart, allowing long-ignored feelings to seep through. She sat down on a boulder and burst into tears.

The man just stood by her and waited as she wept, letting the wave of her emotion break and pass, careful not to interrupt her tears with words.

Dechen looked up at him with swollen eyes. He was about the same age as she was; his overgrown hair and unkempt beard were grey, his mouth missing a tooth or two. Though he wore red velvet boots that came up to his knees, a bakkhu, long robe, an embroidered cap on his head, and spoke in her language, Hoon, there was something about his looks and his accent that told her he was not a local man. Because his eyes were gentle when he looked at her, she surprised herself by her instinctive choice to trust him.

“I am Terry, an Englishman. I have lived in these regions for over thirty years,” he explained.

Dechen laughed out loud, something she hadn’t done since she was a child.

“I thought you were a thief!” she laughed. “How foolish of me to fear losing that which I myself am dumping into the river!”

“Tell me why,” Terry said.

Dechen burst into another heaving, wracking sobbing. Her madness had softened her to the point where she not only appreciated and valued, but craved real contact with a human being capable of listening with attention. Quieting down, she patted the boulder and invited him to sit by her.

“I’m very thirsty,” she said. Terry fetched some water from the river in his kapala, a skull cup, which, along with a knife and a kangling, a horn made of a human femur, hung from his leather belt. Dechen was afraid again – the skull cup was an image from her nightmares. But her thirst made her reach for it and take a long draught.

Dechen told Terry her whole story. He listened without interruption as she spoke, wept, and opened up the sack of her heart, stuffed with sorrow and fear. He was silent a long time and then said to her.

“When I was in England, I too found myself buying too much, accumulating too much, consuming too much. When my marriage broke up – I have no doubt because of my own unconscious feelings about wanting more than I was getting in my marriage, I indiscriminately went through many women. Then one day I asked myself the question, ‘What hunger are you trying so desperately to fill?’ The answer came to me with total clarity: all desperate hungers, like yours, like mine, seek only one food: the divine within and without us. All our striving must be to clear away the weeds that choke the divine inside us. When we find it inside ourselves, we find it reflected in the whole world.”

Dechen was quiet.

“Let me see what you have brought to give away to the river today,” Terry said.

Together they unloaded the sacks. Terry opened one of them and brought out the statue of Vajrayogini.

“Throw her away,” Dechen exclaimed. “I hate her!”

Terry held it in his hand lovingly. Dechen once more questioned his motives, and once more laughed out aloud.

“Don’t hate her,” Terry said to Dechen. “She is your best friend, a guide, a heavenly messenger who has been speaking to you in your dreams and has come to bring you that which no money can buy: peace, joy, happiness, love.”

“She hurt me terribly in my dreams!”

“They were the wounds inflicted by your perverse passions, Dechen.”

“No, it was her! She tried to kill me! She did kill me!” Dechen cried.

“She kills our old, wornout selves that do not serve us any longer, like the tight skins of snakes, that have to be shed if we are to grow into our fullness. I have worshipped her for many years, not as a statue, which is only a representation and reminder, but as an energy that pervades the universe, an energy we have named Vajrayogini. She is the reason why I left England, where I was wealthy, but very unhappy, lost, confused, aimless, to come live in your land, abandoning my religion to find a home in yours. Vajrayogini tramples on distorted desires, worldly wealth, and the small, unconscious ego. She is the one who transformed my many material passions into the light of consciousness; now I live each moment with the awareness of the impermanence of everything, including my body. You already know, I am sure, that drinking and eating from a human skull serves as a reminder of the dream-like nature of our bodies and possessions.

Vajrayogini comes to destroy false illusions, delusions, ignorance, and bestows wisdom. She has blessed you by throwing her thunderbolt at you with full force; your wounds are invaluable; they will turn you towards the path of the Invisible Spirit, the dark and light filled, male and female primal energy of the universe; the energy of which all our lamas, rinpoches, gurus, gods and goddesses are emissaries. Open your heart wide and accept the death she is offering, Dechen; it is the beginning of new life.”

Even though Dechen didn’t understand everything he was saying, she listened intently. All her suffering had prepared her, like soil is prepared by the wounds of the plough, to receive the seeds of wisdom, our only true treasure, which transmutes lead into gold. She looked at Terry with tears in her eyes. Someone had finally taken the time to teach her her own religion, which was so rich in meaning.

“Are you married?” she asked, directly.

“No. I always thought spiritual development was more important than being a householder.”

“And I have always thought that material possessions were more important than a family and love,” she said, sadly.

“I have an idea,” he said, sitting down on a mound and stroking his beard. “Instead of just dumping all your treasure in the river where it will be of no use to the fish, why don’t you use your

wealth to do some good?”

“Like what?”

“Let me see,” he said, scratching his beard and looking thoughtful. “You know, so many pilgrims from so many countries and so many religions – Hindus, Jains, Sikhs, Buddhists, Bönpo, Animists – come to Kailas every season. I myself have traveled to the holy mountain and done the kora more times than I can count. I can tell you from my own experience that the pilgrims have to brave many hardships on the way: hail, storms, snow, tornadoes, avalanches, blizzards, freezing cold, hunger, thirst, and countless other tribulations. I have had to sleep in hollows of ice to keep myself warm; the only habitations on the way are filthy and I couldn’t rest in them because of the fleas and lice. Once I slept with lambs to keep from freezing. I have eaten whatever leaves I could find, and gotten diarrhea and a terrible upset stomach and lain on the snow encased in an inch of ice, my half-starved mule, collapsing with weakness and cold, lying next to me. Once it broke my heart to see the poor beast eating dry dung in his hunger.”

Dechen saw tears in Terry’s eyes as he recalled the event. She realized how her lust to accumulate, her avarice, greed and selfishness had hardened her heart so much that there was no room in it for others. She looked at her mule, standing by the river, loaded down with sacks full of heavy gold, and realized how little, if at all, she had thought about anyone but herself. But seeing the tears in Terry’s eyes, her heart opened wide. Concentric circles of compassion radiated out from it to Terry, her mule, the hardships of the pilgrims and all the suffering people and creatures of the world.

“On my journeys,” Terry continued, “I often wondered why there aren’t any dharmashalas, buildings that provide food and shelter to pilgrims at points along the way. It would be such a caring thing to do. Think, Dechen, of how many dharmashalas we could set up on pilgrimage routes with all this wealth.”

The we in his sentence made Dechen’s heart leap into her mouth. “Yes,” she said, happily. “Yes, let’s do it.”

Terry looked at Dechen. Her small, long face, unmistakably Tibetan, was a mass of wrinkles, her eyes grown smaller with age. He saw beyond it to a beauty that bordered on luminescence, as that of the moon. He smiled at the image of two-ratty looking people in ragged garments, both of flesh and dress, planning a future together.

Dechen looked at the old Englishman who looked like a tiger that had allowed time and age to work their magic on him, and felt a great warmth suffusing her heart.

In the long silence that followed as they sat under the stars, Terry removed the flute made of a human thigh bone from his belt, and began to play it. The, deep, haunting, eerie, harmonious sound singing its urgent reminder of our unshunnable journey to bone and ash, drove home its message and dissolved whatever doubts and resistance remained in Dechen.

They loaded the sack with the gold divinities onto the mule again and tied them down.

“Come,” he said, turning the mule around to face the village. “Let’s give some of this away to needy people, make our plans for the dharmashalas, and get you some nice garments to wear. This is no way for a rich lady to dress.”

“I have many,” Dechen said. “But they may be all moth-eaten by now.”

Day was dawning as they walked together to her house in the village. Released of her heavy burden, Dechen’s steps were light and buoyant as she walked straight and tall beside Terry in the early morning. As the sun poured liquid gold on the trees and rooftops of houses, Dechen, vibrantly aware of the fleeting nature of all phenomena, including herself, looked at everything with new eyes. She found reality pulsing with an intensity she had never felt before.

A sweet love, the kind that can only happen later in life when youthful passions are spent, sprang up between the two people who had known aloneness so intimately. Together, Dechen budhi and Terry budha worked towards their goal, building well-stocked dharmashalas for pilgrims in Darma, Tibet and in the Humla, Jumla and Bajhang areas of Nepal. If a pilgrim looks closely at the surroundings of a temple in Darma, she can see a weathered statue of Dechen budhi, the woman who transformed from a dragon hoarding treasure to a compassionate being capable of sharing and caring for those in need.

About this story:

Collected from Chaudhans, Uttarakhand, by Himani Upadhyaya from Dhiren Budhathoki. Retold by Kamla K. Kapur. Translated into Tibetan by Bhuchung D. Sonam.

The Color of the Name

Original illustration by Rabin Maharjan.

The villagers of Kudang, a mix of Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, Bonpo, Pagans and Animists, with antecedents from India, China and Tibet, and indigenous people, were poor, old, sick, physically incapacitated and chronically hungry. Not much grew in the highlands and food was scarce. Even their goats and yaks were skinny and did not yield much milk. In the winter, the small lake froze and it was arduous work to dig up ice with their feeble bodies and heat it with fuel that was hard to come by. They felt helpless, bereft, abandoned by life because of, they feared, sins committed in their previous lives to which were added sins from the current one. They felt trapped in an endless round of accumulations of bad karma.

The main cause of their unhappiness was their frustration about their inability to undertake the long and difficult yatra to sacred Mount Kailas and do a kora around it. They believed that if only they were able to have a sight of the holy mountain, they would be healed and absolved of all their sins and be happy and rich ever after. They had heard stories, echoed down the generations, about all the gods and goddesses that meditated and sported eternally, joyously around the holy mountain, which was the very center of the universe, the very point, bindu, from which all life originates, and to which it returns.

One cold, overcast day, when the villagers were particularly morose, Sagar, a skinny, lame, half-blind, orphaned child, an outcast of mixed descent, whom the villagers considered a bit crazy, hobbled as fast as he could, followed by his bony dog and lean cat, to the village square and shouted joyously:

“He is coming! He is coming! He’s coming to make us happy! My heart has been calling to him every day. I dreamt about him last night and he is coming up the hill to our village with another man following him! Padmasambhava is coming with a devotee!”

The villagers were convinced the boy, given to flights of fantasy, was just imagining things. Besides, no pilgrims ever visited their village, which was not on the way to Mount Kailas.

“Who is Padmasambhava?” someone asked. “Didn’t he live and die hundreds and hundreds of years ago?”

“Yes, but he is still with us, though he is invisible. His body is made of a rainbow, and his eyes can see the Invisible!”

“Like yours!” someone said to a peel of laughter.

“It’s all true! Padmasambhava was born as an eight-year-old boy in the blossom of a lotus! My father tells me all about him.”

The villagers rolled their eyes. His father had been dead for four years.

Sagar looked at them and said, innocently, “But he comes in my dreams to tell me stories. He told me Padmasambhava’s name means ‘The Lotus born.’ Padmasambhava can fly, and though he has been burned and destroyed, he is always here, and comes to the aid of those in need. He is a savior who kills demons that want to destroy mankind and he performs many miracles.”

“Miracles!” someone scoffed.

“Mother always says that miracles are holes in the cloth of reason. I don’t know what she means, but she says it so many times that I remember her words. Can anyone tell me what it means?”

“Nothing,” someone smirked.

“If we listen carefully and walk on the path shown to us by Padmasambhava, we can drink the blissful drink of amrita, ambrosia!” Sagar exclaimed, his eyes sparkling.

“Amrita! Water would do.”

“But hurry! We don’t want to miss him!”

Most of the villagers went home, but a few, a mix of old and young people and children, followed the boy, his dog and cat at his heels. Sagar took them past the lake that froze solid in the winter, past the arid terraces where nothing grew for lack of rain, to the edge of the village, and pointed to the steep path ascending up to it.

“There! See, by the rock that looks like a bird. I see him clearly, walking with a danda staff, a jhola bag slung on his shoulder, a turban on his head, and a long beard. He is short, and a taller man carrying an instrument on his shoulder, is following him. The short holy sadhu man, in the long beard, is the same person, the very same that came to me in my dream. He laughed, picked me up, and held me near his heart! I woke up feeling so very happy! There he is, closer now, near the boulder that looks like a god with wings. He has come to remove all our troubles!”

The villagers thought the boy had lost his mind. They didn’t see anyone or anything. Several more returned home. Some of the adults and most of the children, however, stayed. They wanted to have some fun with Sagar, whom they bullied as often as they could. They knew nobody would show up and then they could beat him up. They never played with him because even the untouchable children considered him more untouchable than they were.

“Can you hear that?” Sagar said, straining his ears. “They are sitting in the shade of the boulder. The taller man has taken out some instruments, and is playing. They are singing!”

“We hear nothing,” the villagers said.

“Listen! Listen! Listen!” Sagar said, urgently. “You can!”

The villagers turned around and began to leave for their homes. “You have come this far. Come further! Listen with the ears of your soul!” Sagar shouted. “Listen to the words of the song: ‘Don’t be one of those who are born only to die without hearing the music of worship.’”

Then, the strangest thing happened with Sagar’s words. Streams and filaments of a blue, diaphanous mist shimmering with light arose spontaneously around them, wrapped themselves around their heads, entered their nostrils and mouths and lifted them as if they were made of air, and transported their brains with the speed of light into Sagar’s spacious, open, wide innocent heart! Or was it Sagar’s brain? It didn’t matter, for Sagar’s brain and heart were both in the same place, stimulating, questioning, guiding each other towards one goal. Although Sagar didn’t know the name of this goal, he had been moving towards it like an unwavering arrow from the moment of his birth. No, perhaps even before it, even before conception, for our ancestors and guides have taught us that our souls have long roots that extend all the way to the beginning of time.

For an instant the villagers were bewildered and wondered where they were. They had never seen the world like this before.

Looking through the innocent child’s eyes, the landscape was transformed. They saw it suffused with beauty. The bare mountain ranges surrounding a rolling valley lit up by the radiance of the early evening sun vibrated with subtle browns, blues, violets. In the distance they saw the snow-capped peaks standing tall and majestic, like guardians. Their practical, workaday sensibility that had been blind to the beauty all around them lit up with wonder; they began to see and hear invisible, unheard things.

They saw two strangers sitting by the boulder they had seen thousands of times without noticing that it looked like a god hovering from the ground up, wings spread wide in a gesture of protection; they heard drifting up on a current of air the musical strains of a song sung to the accompaniment of strings and the haunting melody of a flute. Though they could not understand the words, the language of music, beyond meaning and sense, penetrated their slumbering, despairing souls. Echoing through the valley, bouncing off the mountains, entering through the portals of their ears, reverberating in the hollow chambers of their hearts, it aroused in them a longing to connect more deeply with life, their own selves, and their gods; they tasted that hunger without which human life, no matter how luxurious and ease-filled, is a grind.

The sound, pouring into their ears like amrita, stilled all the noises of worry, anxiety and doubts in their heads. It unfurled a silence they had never heard before, nothingness, a shunya opening petal by petal like a lotus, space upon limitless space, empty space, without stars or clouds. In that silence something stirred, like a slumbering seed in the ooze of mud and waters. It awakened them to the sweetness of a long-forgotten dream: a path visible through the surrounding darkness winding soulfully up into the unknown to a magical perch, a perspective that turned every sorrow into mulch and slush from which blue lotuses bloom.

“They are singing, ‘Remain awake and aware. Do not fall asleep!’” Sagar, who understood all languages of the heart, translated for them. The words were like bolts of blue lightning that tore through thick veils in their minds. Passion awakened in their hearts. One young girl remembered how she used to sing when she was a child; another recalled with what joy she used to spin and weave; a young, how he used to collect colorful pigments from the mountains and paint images of gods and mandalas on stones; another remembered his desire to become a herbalist and curing sickness. In that instant they resolved to pursue their long-forgotten dreams.

When the strangers were done singing, they picked up their bags, musical instruments and resumed their climb up the hill. Though the path was steep, they climbed up lithely, like birds cruising on an invisible current of air.

The strangers came closer. Though they had obviously undertaken a long journey, they looked fresh, vibrant, glowing with health and well-being.

They were not dressed in any garb that would distinguish them as belonging to any religion, though the taller one may have been Muslim, by the cut of his beard. They wore no saffron clothes, rudraksha beads, or matted hair to indicate they were Hindus; no maroon robes, shaved heads and begging bowls, like of Tibetan lamas. Though their countenances were radiant, like the faces of gods, they looked just like ordinary men in ordinary Indian clothes. Sagar ran to the shorter of the two men, the man he had met in his dream, and threw himself at his feet. The stranger helped him up and Sagar instinctively clasped his neck with his arms and clung to him, sobbing and weeping with joy. Though the villagers fed Sagar now and then, nobody, other than his parents, had ever embraced him like this. One day he ate leftovers in one home, the next day in another, and he slept with the yaks on the straw on someone’s ground floor.

Sagar’s dog leapt on the strangers, and his cat purred and rubbed herself against their legs.

The villagers, moved by the sight of the holy man embracing the ragged orphan, bowed and touched his feet. As they did so, they felt remorse at their treatment of the orphan child. They also touched the feet of the other stranger, who shone brightly from long proximity with the Enlightened One.

Without a word, the villagers followed Sagar, his dog and his cat galloping ahead of them, as he led the holy visitors back to the village. Passing by the terraces the stranger with the long beard took a handful of some grains from his bag and scattered them wide. On the next terrace, he took out a ball and threw it to Sagar, who caught it. They played so vigorously and joyfully that the other children who had accompanied their parents to the edge of the village, children who had never played with Sagar, joined them, jostling each other, running and shouting.

Later, on the way to the village, the stranger stood by the lake, plunged his danda with seven knots in it into the waters and stirred it, as if churning something up, laughing all the while. By the time they reached the village, a sweet rain had begun to fall. Everybody rejoiced, for they hadn’t had any rain that year and the buckwheat and barley were drying up. Leaping and skipping, Sagar proceeded to the barn that he called home. A few roosters and hens greeted the throng, for that was what the meager few had become.

The dog and the cat that had followed Sagar to welcome the guests curled up on the straw in the barn that the boy called his bed, and fell asleep. When it was very cold, Sagar burrowed beneath it to stay warm.

The villagers surprised themselves by running to their homes to fetch precious food for the strangers. They discovered to their surprise and delight how much more food than they had thought they had. They brought buckwheat and barley cakes, tea leaves and yak butter for tea, dried yak meat, not just for the strangers, but also for Sagar and the others, and even something for the dog, the cat, and birds. Some brought extra mattresses, quilts, and hand-woven blankets.

Everyone partook of the feast. Even the holy stranger with the long beard ate heartily and moderately. Then he lay down on one of the mattresses, and fell fast asleep.

The villagers asked the taller stranger his name. He said he was Mardana from Punjab. “Most people call me Bhai Mardana.”

“Bhai Mardana Lama,” Sagar bowed to him. “And he is Guru Nanak,” Bhai Mardana said.

“Padmasambhav Rinpoche Nanak Guru,” Sagar said, prostrating before him as he slept. “Does he kill demons?”

“All the time,” Mardana laughed. “But the demons he teaches us to subdue – not kill; for they are unkillable – are the demons in our own minds.”

“What is your relationship to Guru Nanak Rinpoche?”

“I am nothing if not the minstrel, companion, servant and devotee of my Guru. And he calls himself his Beloved’s minstrel and slave. The Beloved has made him his instrument and sings through him. Baba Nanak doesn’t speak much these days, unless he has to.”

“Who is the Beloved?”

“The One who lives in all hearts, regardless of caste, color, race, class, nationality.”

“But what is the One’s name?” someone queried.

“The One is Nameless, though people call it by different names. Some call it Energy, some Mystery, some the Universe. The One has as many names as there are people who worship them and call them Shiva, Brahma, Durga, God, Tara, Shakti, Durga, Bhagwan, Allah, Rab, Waheguru, and thousands of others.”

“Is the One a man or a woman?” a woman asked. “Both and neither,” Bhai Mardana replied.

“Yes, yes, my mother says that, too. She made a painting, there, that one, Shiva and Parvati, together, one body, one mind, one soul.

She called it Ardhanarnari.” Sagar went to the wooden wall of the barn where he had tacked his mother’s paintings, and pointed at one of them. In the light of the lamp the villagers saw one body, half male, half female in its dress and anatomy, the former blue, unclad, the latter green and adorned with jewels. Their boundaries were fluid, merging into one another, dancing, changing, getting more and more abstract, almost invisible towards the top of the painting where waves of clouds dissipated into an undifferentiated blue.

“Mother father God!” Sagar said, exuberantly. “Exactly!” Bhai Mardana said.

“What is your religion?” they asked.

“The religion of Nature and its Maker: the religion of the Creator of rivers, wind, fire, mountains, lakes, all of Nature inside and outside us. We are slaves of Banwari, the Lord Creator of the Universe, the Husband for whom all Nature, animate and inanimate, is bride, adorned in all her finery for her wedding night. We travel all over the world to worship beauty and to meet people from all countries. Whenever Baba Nanak sees any awe-inspiring place, he goes into a deep trance, marveling at and praising the grandeur of this Earth, and falls in love all over again, with the intensity of first love, with the Beloved. We have traveled all over the world, seen many places, met many people, seen their customs and rituals, and though there are different countries, different ways of living and worshipping, Baba knows the beautiful Earth, mother of us all, though she is cut off and parcelled into small countries, is one country, and all the people, in all their amazing distinctions, beliefs, and many-colored variety, are one people.”

“What do you call yourselves?” Sagar asked. “Sikhs.”

“What does it mean?” The villagers, hungry with questions, asked. “It comes from the Sanskrit word shishya, which means a student devoted to learning in all its forms. Above all, a Sikh yearns passionately to know, examine, explore the unknown country inside himself or herself, for that is the ultimate knowledge. Baba knows that this is the inward path that takes us to the Beloved.”

“What else do you believe in?” someone asked.

“Baba tells his followers to live their lives fully. He himself is a farmer, a guru, a husband, a father, and performs all his roles well, participates in and engages with every aspect of his life dispassionately and detachedly. He lives like a hermit amidst life, like a lotus, unsullied by the dirt and slime out of which it springs. He tells his devotees to earn their living honestly, share what they earn with others, and treat everyone equally. Baba also says don’t get stuck in superstitions. Live bravely and without fear. Use your mind but know its limits. Use the senses but know their boundaries, and above all, remember! Remember, remember the Great God’s Great Name, especially when you are suffering!”

“Why?” a child asked.

“Because when we remember someone, that person comes alive in our memories and our minds, becomes present; because as soon as you remember the name of your Beloved, the Beloved is there! Repeat it whenever you can, make it your friend, so when you can’t even remember to remember it, when you are in the deepest distress, it will remind you to remember. Ah, the name of our Beloved is our closest friend whose long, strong hand reaches down through the layers of thick snow when you are buried in an avalanche, plucks you to safety, and lights a fire in the blizzard to warm your bones! On our way to Mount Kailas we encountered a blizzard and let me tell you…”

“You’ve been to Mount Kailas?” the villagers asked in a chorus. “Yes, we’re returning from a yatra, a pilgrimage to Mount Kailas and Lake Manasarovar, where Baba and I swam with the fishes,” Bhai Mardana said.

As soon as the villagers were reminded of their unattainable desire, the source of all their misery, a swirling, whirling blizzard with icy, furious winds flung them out of their warm, cozy corners in Sagar’s expansive soul and hurled them back into their own unhappy brains. The storm that blew them out was nothing like the hurricane in their heads that raged furiously with wailing sounds, deafening them with its frightening cacophony. As they sat in the barn a change came over their bodies, too. Their limbs and bodies collapsed, slumped, their faces became long, their eyes mournful. Their moaning, groaning and whining began as they complained to Bhai Mardana about their miserable lives, their feeble and diseased bodies, their inability to undertake the pilgrimage that would cure them of their diseases, and absolve them of the sins accumulated over lifetimes.

“So that’s why both of you are pure and radiant!” someone said bitterly. “Your sins and curses dissolved in the sacred waters and you have been made holy by your pilgrimage! Well, welcome to our unholy village.”

“Kailas and Manasarovar are splendid sights, indescribable, but they are no holier than any other awe-inspiring place in Nature, no holier than your own village, homes and bodies,” Bhai Mardana said. “Blasphemy! Mount Kailas is the most special place in the whole world. It is the center and navel of the universe!”

“There are as many centers of the world as there are people and creatures,” Bhai Mardana said. “Mount Kailas was and is a mythic metaphor before it was ‘real.’”

“What do you mean? What is a metaphor?”

“A metaphor is a physical object, like Mount Kailas, that stands for a truth that cannot be described any other way. Mount Kailas stands for what Hindus, Buddhists and Jains call Mount Meru, or Sumeru, around which the sun, planets and stars are said to circle. Some say Meru is in the middle of the Earth; some say it is in the middle of an ocean; some say it is the Pamirs, northwest of Kashmir, some that it is Mount Kailas; most believe it is the place where all the gods live, the high mountain from which humans can climb into heaven and paradise,” Bhai Mardana explained.

“Yes, we believe this, too!” the villagers cried with one voice. “But we will never be able to reach it! We are doomed!”

“But we must not make the metaphor the thing itself. If you worship an image made of stone, or a mountain, and forget that it is only an image, a representation, a reminder, then you close yourself off from the boundless, imageless, formless One that no metaphor can describe, the One who is not confined to any one thing or place. We must question our beliefs when they limit us and the Limitless One. On my way to Mount Kailas I was wondering what the word ‘Meru’ meant. I asked many priests and holy men but none knew. And then one day I realized that it must be an affectionate variation of the word ‘mera,’ mine. ‘Mera’ has a lot of ego in it, but ‘Meru’ has sheer love. And in a way, it is all mine. In this sense, the whole universe is mine. This belonging happens when I enlarge my ego, like a balloon. But unlike a balloon that bursts as it enlarges, the ego stretches to include everything there is. Everything. Nothing left out. This is who we truly are, tiny but at the same time large enough to house the whole big universe!

Though people think Meru, or what you call Mount Kailas, exists in different places, yogis know it exists inside us. Enlightened ones of all times have known that our spine, which they call merudanda, the staff of Meru, is the axis and center of the world. We have to learn to climb from our baser instincts to the higher ones; from the bottom of our spine, where Mara and his many demons live, up through the nodes and knots in the spiral of our spine that lead to the thousand- petal lotus on top of our skull. This is the true pilgrimage, what Baba calls ‘the pilgrimage to yourself.’ It is this journey that makes us aware of our sins and with the Beloved’s aid, makes us pure.”

“Easy for you to say all this because you have been there,” someone said angrily. “But we are physically debilitated, poor, hungry, and very unhappy. Our crops are blighted every season; the winters are so harsh that we lose many from our community; our children don’t have enough to eat and many die before their first year.”

“We have rotten karma, we are decayed from the inside out, stained and grimed with sins. We will never get to Mount Kailas, the Dharma Dwar, the gateway to heaven, that will make us healthy and whole again,” a woman began to keen.

“Baba says in one of his songs: When your clothes are soiled and stained by urine, soap can wash them clean. But when your mind is stained and polluted by sin, it can only be cleansed by the Color of the Name.”

But the woman continued to cry. Bhai Mardana despaired. He felt the villagers hadn’t heard or understood a word he had said. Only Sagar was listening to him intently, eating and digesting all his words. Perhaps he had not been sincere enough, or sermonized too much, Bhai Mardana thought. He doubled his efforts.

“There is hope,” he said. “I too was full of sins. I have doubted, cheated, lusted, raged, envied, coveted, held ‘me’ and ‘mine’ too tightly, been proud, arrogant and ungrateful. But Baba has helped me to become what I am, a gurmukh, one who faces the Guru of all Gurus, God himself, instead of his own ego. He has also taught me that what I was truly seeking beneath my searching for wealth and fame was the fountain of amrita that is within me. It is wherever I go. You don’t need to go anywhere to be happy and healthy. Now that Baba has come to you, you have to trust that all will be well. You too will learn that your village, your home, your body is blessed and beautiful.”

“What’s so blessed and beautiful about it? What do you see here?” “You have to learn to open your eyes,” Bhai Mardana said.

“But our eyes are open,” they replied. “We are not blind!”

“See?” Bhai Mardana said, looking at the gallery where Sagar had hung his mother’s paintings. He pointed at an image of two eyes shaped like fish and a third sitting calmly above them.

“See with your third eye, the one that unites our conflicts, our double vision and shows us the Truth. When you see through it, your sorrows become lotuses, and your curses turn into gifts.”

“Tell us how to do it,” the villagers pleaded. “We will work very hard to open our third eye.”

Just then a loud chuckle was heard from Baba Nanak as he turned over in his sleep. Bhai Mardana shut his eyes and was silent, as if listening to something his guru had just conveyed to him. Then he opened his eyes and said, “Effort is important but will get you nowhere. See, I have been making so much effort to explain all this to you, but I am a fool. I forgot something very, very essential. I should have begun with a prayer to ask the magnanimous Fulfiller of Dreams to help me in my efforts. Without the One’s aid, all our efforts are straw in the storm.”

“We pray a lot but nothing ever happens,” the villagers complained. “But how do you pray?” Bhai Mardana asked.

“With our mouths, of course.” Bhai Mardana laughed.

“Learn to pray with your heart. Be present. Know that the One you address is present, more present than what you see with your two eyes. ‘He is! He is! He is! He is, He is – I say it millions upon millions, millions upon millions of times,’ Baba sings ecstatically. The Truth of the One is Guru Nanak’s most important message. Remember that when you take even one step towards trying to open your third eye, the Beloved, if you have remembered to love the Lord of the Universe, to ask for His aid on your pilgrimage, He will come towards you a thousand steps to help you to see. There are many, many precious rewards for our love. Baba says, ‘If you listen to just one thing the guru says, pay attention to and act on it, keep it in your ear and heart, your mind will become a treasury holding precious rubies, pearls, coral and diamonds.”

“Is it really true that the guru can give us wealth and precious stones?” someone asked.

“Our real wealth, the highest and best, is the One, in loving whom we can get both material and spiritual gifts, the most important of which is learning to see with the Third Eye. It is the Magical Eye that can turn ugliness into beauty, poison into amrita, and, as Baba sings, ‘our sorrow into the most health-giving of tonics.’ There are ways of seeing things from a height, as if from a star, as if from the pinnacle of Time that is far, far larger and vaster than our own past, present and future. Let me give you an example.”

Bhai Mardana reached for his bag and took out a handful of seashells, worn smooth with age, some brittle, some whole.

“I know!” Sagar said. “They are called ‘shells’ and they are found on the ocean floor.”

“What is the ocean?” someone asked. They lived so far away from the ocean that they hadn’t even heard the word, let alone understand the concept. But somehow, somewhere, in the deep recesses of their memories, the ocean roared in their dreams.

“It is what my name means, Ocean!” Sagar said excitedly. “It is a vast body of water that . . .”

“Like Manasarovar?”

“Nothing like Manasarovar! There is much more ocean than there is land on this earth!” Sagar said excitedly. “My parents told me all about it! The ocean is so deep that there are mountains in it, large mountains and volcanoes. We know very, very little about it, it is mysterious and without limits, like God. They told me to always remember what my name means, that I have an ocean in my heart, and I must never forget it! Maybe that is what Rinpoche Mardana is talking about! Even though I have never seen it I feel it in my heart!”

“How can that be? We haven’t seen it!”

“We have to admit to ourselves that many things exist that we can’t see with these eyes,” Bhai Mardana responded. “Did you know, for example that your high plateau and Mount Kailas were once the ocean floor? These shells are proof of it. Baba and I collected them on our way to Mount Kailas.”

It took a while for the villagers to understand what Bhai Mardana was saying. They were silent a long time, trying to stretch their minds to envision Mardana’s words.

“Nothing is forever on this earth. Mount Kailas, too, one day, will be beneath the sea again. But the mythic Mount Meru will never perish. It is within us. But I have been talking too much. Come, let us meditate and pray together.” Bhai Mardana sat cross-legged, and instructed the villagers in a few brief sentences how to pray and meditate. His voice was gentle and full of compassion as he said, “Sit comfortably, shut your eyes, know that we are in the presence of the One who is within, like breath, and surrounds us, like air. If many thoughts crowd your mind, let them be, but gently steer yourself back to the presence of the One. Be grateful for what you have before you ask for what you want. Today, ask for help to embark upon the journey of all journeys, the journey to the home of the Beloved in your heart, the Beloved that erases suffering.”

Their brief sojourn in Sagar’s trusting and hopeful heart had made the villagers want to return to that place where they saw, heard and felt things that had filled them with hope. They were sick of being sick and sorrowful. They did as they were told.

When they opened their eyes after meditation, they felt something had shifted in their consciousness. They had moved on from their locked in, habitual mode of thinking and feeling. Their minds, which had been stagnant for so long, were flowing again.

Bhai Mardana yawned. It had been a long night, and he had talked too much. He smiled to himself as he recalled the sound of Baba’s chuckle. In the silence that followed he had asked for help to help the villagers. After all, that was the reason Baba had suddenly changed course in the middle of his travels and headed towards Kudang. He went where he was needed.

The villagers, relaxed into peace, began to yawn, too.

“I have a message to convey to you from Baba,” Bhai Mardana said, as the villagers began to touch his feet before leaving for their homes.

“Tomorrow morning, when the night is drenched in dew, and the stars are still twinkling brightly in the sky, gather in the center of the village and follow Baba and me to the crest of the hill that separates your village from the next village, Sosa. Baba will take you to the dharma dwar, the gateway and threshold of all that is sacred. By visiting it whenever you feel you need to, you will dissolve your suffering. It is a place holier than Mount Kailas and more sacred than Manasarovar.”

Although their old minds still whispered to them that the crest was too high to climb and that they would never be able to do so, the villagers, eager to follow Bhai Mardana and Baba Nanak on the path that would give their suffering wings, agreed.

At dawn the next day, all of them, including some old people and children, assembled in the center of the village. The dog and cat were there too, excited at the prospect of an adventure. They too were eager to follow a path that would help them reincarnate as humans in their next life. Guru Nanak, whom the villagers now called Padmasambhava Rinpoche Nanak Guru, was vital and energetic. Bhai Mardana Lama too was glowing with energy and health. More than anything else, their aspect and appearance, conveying well- being and vitality, made the villagers trust them.

After a prayer led by Bhai Mardana, the villagers took their first step in the direction they had never gone before. Although some of the villagers huffed, puffed and groaned a bit, they all made it up the hill to the crest. They were amazed at looking down the path they had climbed, it seemed in retrospect, so easily. They saw their village as if for the first time. How lovely, cozy, heartwarming it was, their collective home, tucked into the sides of their mother mountain, as if in the folds of Parvati’s protective body.

The villagers felt invigorated, healthy, alive after the exercise. Their bodies sang with gratitude and joy. This, they knew, was the purpose of the ascent, for Mardana Lama had already told them they contained Mount Kailas, the axis, the center of the universe where gods meditated and sported. The lesson was driven home on the summit of the crest.

Morning had not yet dawned though there was enough light to see by. It was the brief and fleeting time of day when gates to others world are wide open for all to walk through. The indigo sky was still embroidered by stars as the holy current of healing and awakening dawn breezes, that sages in India called malyanil, blew gently down from the peaks of the high mountains, caressing their limbs and entering their lungs.

Guru Nanak pointed his staff to a large arch in a huge rock eroded by the elements of wind, water and time. Through it towered snow- capped peaks that were so high that their tops were veiled with clouds and mist, peaks unseen by any human eye. The sight filled the villagers with wonder, and as one body, they bowed down in worship and awe that something existed so close to them without their knowing it. The sight opened their hearts and minds to humility: how little they knew! How closed and blind their sight had been as they huddled in misery in their village of Kudang, without venturing out of the borders of their minds!

The insight, accompanied by harmonic chords of music, filled them with amazement at the mystery of their own existence within the presence of the universe. They turned around from the sight of the peaks to see that Bhai Mardana had taken out the rabab and was playing it. Baba cleared his throat, shut his eyes.

A note, emanating from somewhere deep within him, was carried on the waves and currents of air all around them till the mountains, valleys and high peaks echoed with it. It drifted back into their hearts and minds, enlarging them in a way they had never dreamed possible. The note, unfurling in its many permutations, under and over tones, morphed like a wave into another note that reflected and contained it, and then another, and another, all strung together like prayer beads on a string, till it became an irresistible melody that penetrated, possessed and suffused their beings with its magical, transformative power. All their suffering and Bhai Mardana’s sermon the previous night had ploughed, cleared and prepared their hearts and minds for Baba’s song and message, for blessed music and winged song reach to the depths and pinnacles of our soul where no words can go. They did not understand the words Baba sang but since they had already imbibed its lesson through Bhai Mardana, the song worked its magic in their souls. They would never be the same again.

They understood that though the dharma dwar existed for those who wanted to make an external pilgrimage, they didn’t need to go anywhere to reach the fountain of healing within them. All they had to do was sit in the comfort of their own homes, meditate the way Bhai Mardana had taught them to, and bathe in the holy waters of Manasarovar at the foot of Mount Kailas within them.

Bhai Mardana and Baba Nanak got up, picked up their bags and began their descent to the next village that needed their presence to open its eyes. Sagar was about to cry but understood instantly that he would never again be separated from his Padmasambhava, who had come to transform his life.

The villagers strained their eyes to follow them down the long and visible path to Sosa, but they never caught sight of the strangers again. They had disappeared as if they had never been.

In the days, months, years, and decades that followed their sudden appearance and disappearance, the villagers saw green shoots of rice spring out of the soil in the terraces that Rinpoche Nanak Guru had strewn with seeds of rice; the lake didn’t freeze where their holy visitor had roiled its waters with his danda; the child Sagar grew up and funds arrived magically for him to open up a gompa, a small temple of religious learning; the villagers, much more prosperous than before Baba Nanak paid them a visit, told, retold and embellished the story of the visit of the holy ones to their children and grand- children. They and their descendants often wondered if the story was just a myth and a dream – a dream that had changed everything.

About this Story:

Collected from Chaudhans, Uttarakhand, by Himani Upadhyaya. Retold by Kamla K. Kapur. Translated into Hindi by Chandresha Pandey.

You Don’t Die Till You’re Dead

Original illustration by Rabin Maharjan.

The following in an excerpt of the full story…

A herbalist, a stone carver and a cook were very close friends, even though the herbalist was a Bonpo, the stone carver a Buddhist and the cook, a Hindu. They had a lot in common: they were weary of their wives and their children’s demands. Their wives nagged them to get better and bigger houses, better kitchens to cook the family meals, more and more land to grow fruit and food, better conditions for their children and their families, while the children were fighting bitterly among themselves and with their parents for the family’s inheritance.

All three felt tormented by their wives and mauled by family conflicts. They decided that life was not worth living on these terms, and what they really wanted was to renounce “Maya,” the illusion of the material world, all attachments and possessions, and take a holy vow to go on a quest to affirm, protect and worship the sacred in nature, undertake a pilgrimage to the holy Mount Kailas whose one glimpse washes away sins, enlightens the soul and elevates it above attachments and afflictions. They would gain merit by circling the inner, more difficult path at its base, then spend the rest of their lives meditating, the way Lord Buddha had done under the Bo tree, or Shiva had done in the lap of the sacred mountain near the holy lake, Manasarovar. Lord Buddha, too, had left his young, beautiful wife, Yashodara, their son and kingdom. Lord Shiva had shunned the comforts and struggles of a household, left his wife, Parvati, for solitude and peace in the very navel of Mother Earth. Both had learned to control their minds so strictly that they did not stray to material things.

They decided, as many before them who had taken the same path to liberation, to perform their own funeral rights as a symbolic gesture of dying to the world, to everything profane including their bodies and their incessant needs and cravings, before leaving. In the middle of the night when the villagers and their families slept, they made their way to the village cremation spot by a pool on the banks of the river. They placed effigies of themselves on piles of wood that served as funeral pyres, poured ghee on the effigies, and set them ablaze. Throughout the burning they chanted mantras and prayers for their own souls. When the effigies turned to ash, they took fistfuls of their own remains and consigned them to the river in a ceremony that included the lighting of lamps and feeding the fish the cooked rice and lentils they had brought with them in lieu of feeding the villagers, to whom they owed a feast on their deaths.